Ideas at the Speed of Horseback

November 14, 2016

Detail of this early 16th Century Bronzino portrait of a young gentleman features a surprising new invention that would soon take the world by storm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, portrait of Agnolo di Cosimo di Mariano, H. O. Havemeyer Collection.

It’s next time again.

You are most likely a book lover. The feel of that slightly rough page, the imprint of that deep black type. Maybe it’s a leather cover or gilded edge on a favorite title that brings a smile. Maybe you are also happy to become absorbed in books on your iPad or smart phone. Whether antique, hardback, paperback or electronic, once books get into your life, it’s very hard to imagine your life without them. David Foster Wallace claimed, “I do things like get in a taxi and say, ‘The library, and step on it!’ ” He also said, “Reading is the first addiction.” But, as the old story goes, it wasn’t always so.

At the push of a button, and with almost no effort on my part, the ideas in this Blog will rocket around the world. These days, it is not unusual for me to post a picture on my Instagram account and get a comment back from a friend in Turkey twenty seconds later. I take it completely for granted. But there was a time when the fastest an idea could travel was the speed of a courier on horseback. Just imagine the implications of the flow of information in an unplugged, unprinted world. No newspapers. Obviously no TV, radio or telephone. No photographs. No magazines. Without wires, the transfer of information was slow and physical. Just a hundred and fifty years ago it took eleven days for the news of Lincoln’s assassination to reach London. Now, millions of people learn of a new idea within seconds. Back then, the transmission of an idea took its own sweet time.

Front entrance to the Gallerie Accademia in Venice welcomes visitors to a show on one of Venice’s most impressive inventors, Aldo Manuzio who founded the famous Aldine Press.

I pondered these things as I attended two wonderful exhibitions about books on opposite sides of the Atlantic. The first, in Venice, at the Gallerie Accademia, Aldo Manuzio – Renaissance in Venice, examined the fascinating career of the man who is largely credited with inventing the pocket-sized printed book. The second, Beyond Words – Italian Renaissance Books, in Boston at the Isabella Stuart Gardner Museum, featured breathtaking illuminated manuscripts, and also some of Aldo’s precious printed volumes. Because I had been studying and thinking about the implications of his invention, they appeared to me, resting comfortably in the glass cases of the Boston exhibition, like old and dear friends; precious relics from a distant Venetian past.

Illuminated manuscripts under glass at the Isabella Stuart Garner Museum which has one of the largest collections of rare books and manuscripts in Boston

Before Aldo and his colleagues changed the world forever, books were painstakingly crafted, one at a time, with pen and ink. Every single one an expensive, original and unique creation. Yes, books were copied but not at all in the sense we use that word today. If you are interested, this process is perhaps best described in the book Swerve – How the World became Modern by Stephen Greenblatt. In his excellent book, Greenblatt memorably describes the exploits of the humanist scribe, Poggio Bracciolini (1380 – 1459), whose magnificent miniature calligraphy is the stuff of priceless masterpiece manuscripts in the world’s finest book collections.

On display in the Boston show is this painting from the Harvard Art Museums by Matteo di Giovanni of St. Jerome in his study.

The show at the Gardner featured some of these treasures and as you looked at them your brain just sort of short circuits at the amount of painstaking work going into the creation of single page, let alone an entire volume. Next to these colorful, illustrated and gilded, one-of-a-kind masterworks, Aldo’s black and white tiny manufactured books look sort of ordinary and humble, but the technological leap they represent is like the difference between riding a horse and driving a Ferrari.

This 15th Century Book of Hours was most likely made in Amiens France for a wealthy noblewoman. From the Boston Museum of Fine Arts Manuscripts Collections.

Try to imagine a world without printed books. It’s almost inconceivable. Imagine if almost everything you knew came only from what you heard directly from the lips of another person. To imagine this you have to slow down. As The English Patient himself says to the reader speeding through an out loud recitation of Kipling, “Read him slowly, dear girl, you must read Kipling slowly. Watch carefully where the commas fall so you can discover the natural pauses. He is a writer who used pen and ink. He looked up from the page a lot, I believe, stared through his window and listened to birds, as most writers who are alone do. Some do not know the names of birds, though he did. Your eye is too quick and North American. Think about the speed of his pen.”

Before the printed book, most people could not read. Books were rare and expensive and copied out by hand. Knowledge traveled from place to place through hand writing carried by hand from place to place. This is ferociously hard for us to fathom. Why? It’s because our world is so vastly different and equally mind boggling but at the opposite end of the speed spectrum. Consider this: in the next 24 hours, 23 billion text messages will be sent. Sixteen million texts were sent in just the past minute.

This idea of how different the world was sneaks up on you at odd moments. It first caught my attention in a film I saw about music. In it, someone described the fact that until the middle of the nineteenth century (when it took eleven days for that urgent news about Lincoln to reach London) every piece of music you ever heard was a live event performed by an actual musician. I don’t know why this idea blew my mind the way it did but as I thought more and more about the invention of the pocket book, a similar feeling of dumbfounded appreciation dawned on me. With the pocket book, ideas became portable. With the pocket book, knowledge became affordable. With the pocket book, mass culture finally found its vehicle. No wonder Aldo Manuzio was so passionate about his technology. He was a man in love with ideas and he must of sensed the vast inherent power in what his presses were printing.

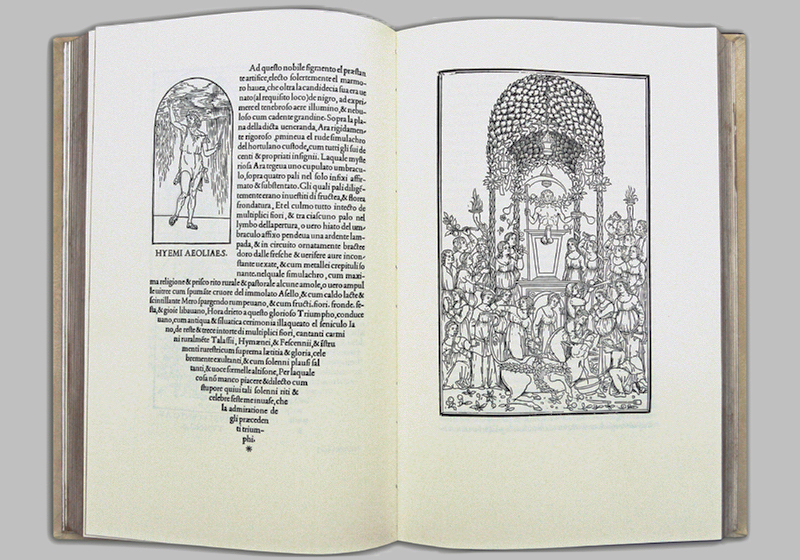

This book the, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, was prominently featured in the Venice exhibition and was described in its day as the most beautiful book in the world. Aldo Manuzio must have been partcularly proud of the decorative typesetting.

Cesare De Michelis, in the catalog of the Venetian exhibition explains, “The book [is] a spiritual place, a treasure chest of wisdom where knowledge and memories of individuals and communities are condensed and take shape blending and mingling with that simple and complicated object…so that every reader could finally have a copy all to himself.”

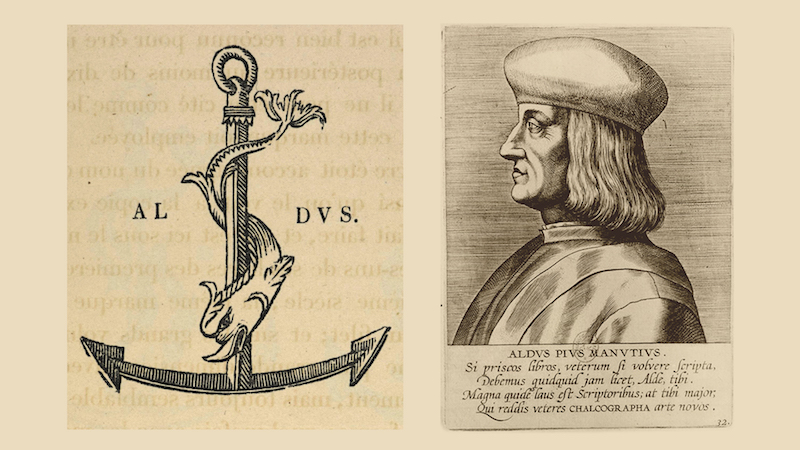

The famous logo of the Aldine Press features an anchor and a dolphin, a visual depiction of the latin phrase, “Festina Lente” (make haste slowly) a perfect sentiment for craftsmanship and the pleasure of reading. 17th Century portrait of Aldo Manuzio, Bridgeman Images, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris

Aldo’s dream was to manufacture a beautiful well-made book you could hold in one hand. He had a name for it – enchiridia, the one-handed book. Before Aldo’s time there were certainly were small hand written manuscripts, usually of religious texts, laboriously copied by monks in monasteries. But he and his circle of intellectuals wanted to transmit ideas faster than the monks could write. He invented italics by copying the particularly beautiful hand writing of one of the monks whose penmanship he particularly admired. This allowed him to fit more words on the printed page and also helped him to shrink the size of the book so you could hold it more easily.

Oil portraits by Parmagianino and Lorenzo Lotto featured sitters proudly displaying their new passion. Portrait of a Man with Petrarchino is from a private collection. Portrait of Laua da Pola is from the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan.

The Venice exhibition ended with gorgeous Renaissance oil portraits of fashionable men and women holding this amazing new invention. As I looked at them, they looked back at me. Our eyes met across the centuries. Their expressions seemed to say they were proud of their new technology. They wanted to hold it in their hand as a symbol of how up-to-date they were. The enchiridia was every bit as cool as the latest cell phone. Holding a book said to the world you were not only modern but you belonged to a new educated elite. The titles were often new editions of ancient works. Powerful old ideas in a very new high tech package.

If you are in Boston don’t miss the Renaissance book shows happening all over the city. The Beyond Words exhibition is on until mid-December in three venues, the Isabella Stuart Gardner Museum, Harvard’s Houghton Library, and the McMullen Museum at Boston College. The Aldo show in Venice has now ended but I think it was the best show the Accademia has put on in recent years. Venice, in this instance, had a very unfair advantage. It was nothing short of breathtaking to walk out of a show on the meticulous creation of 16th century books onto streets and vistas filled with plenty of 16th century buildings that Aldo himself had passed on his way home. No doubt he had one of his latest published books clutched tightly in his hand.

Until next time with much love,

Tommaso